Origins of Shingon Buddhist Art Using Gold and Clouds

The arts of Japan are profoundly intertwined with this state'southward long and complex history. They are besides often in dialogue with artistic and cultural developments in other parts of the world. From the earliest aesthetic expressions of the Neolithic menses to today's contemporary art—hither is a brief survey to get y'all started.

Delight note that while the material is organized chronologically, information technology highlights major themes and introduces makers and objects recognized as especially influential.

Jōmon period (c. 10,500 – c. 300 B.C.Due east.):

grasping the world, creating a world

"Flame-rimmed" deep bowl, Middle Jomon period (c. 3500–2500 B.C.E.), earthenware with cord-marked and incised ornament, thirteen inches tall (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Jōmon flow is Japan's Neolithic menstruation. People obtained food by gathering, angling, and hunting and oft migrated to cooler or warmer areas every bit a result of shifts in climate. In Japanese, jōmon means "string design," which refers to the technique of decorating Jōmon-catamenia pottery.

Equally in most Neolithic cultures around the earth, pots were made by hand. Vessels would exist congenital from the bottom up from coils of wet clay, mixed with other materials such every bit mica and crushed shells. The pots were then smoothed both inside and out and decorated with geometric patterns. The decoration was achieved past pressing cords on the malleable surface of the even so moist clay trunk. Pots were left to dry completely earlier being fired at a low temperature (most likely, just reaching 900 degrees Celsius) in an outdoor fire pit.

Later in the Jōmon period, vessels presented ever more complex decoration, made through shallow incisions into the moisture dirt, and were fifty-fifty colored with natural pigments. Jōmon-period cord-marked pottery illustrates the remarkable skill and artful sense of the people who produced them, too every bit stylistic diversity of wares from different regions.

"Goggle-eyed"-type dogū figurine, belatedly Jōmon period (ane,000- 400 B.C.East.), excavated in Tsugaru urban center, Aomori prefecture, Nippon, clay, H. 34.two cm (Tokyo National Museum, Japan)

Also from the Jōmon menstruation, clay figurines have been found that are known in Japanese as dogū. These typically represent female figures with exaggerated features such as wide or goggled eyes, tiny waists, protruding hips, and sometimes large abdomens suggestive of pregnancy. They are unique to this flow, equally their product ceased past the 3rd century B.C.East. Their strong association with fertility and mysterious markings "tattooed" onto their clay bodies advise their potential use in spiritual rituals, perhaps as effigies or images of goddesses. Besides dogū, this period also saw the production of phallic stone objects, which may accept been a part of the same fertility rituals and beliefs.

Images of the female body as symbols of fertility are encountered in many parts of the world in the Neolithic menstruum, presenting features unique to the regions and cultures that produced them. The preoccupation with fertility was increasingly twofold, namely the fertility of women and that of the land, as people began cultivating it and transitioning to a settled agronomical society.

Yayoi period (300 B.C.E. – 300 C.E.):

influential importations from the Asian continent (I)

People from the Asian continent who were cultivating crops migrated to the Japanese islands. Archaeological evidence suggests that these people gradually absorbed the Jōmon hunter-gatherer population and laid the foundation for a society that cultivated rice in paddy fields, produced statuary and iron tools, and was organized co-ordinate to a hierarchical social structure. The Yayoi catamenia'south proper name comes from a neighborhood of Tokyo, Nihon's upper-case letter, where artifacts from the period were showtime discovered.

Yayoi-period artifacts include ceramics that are stylistically very dissimilar from the cord-marked Jōmon-menses ceramics. Although the same techniques were used, Yayoi pottery has sharper and cleaner shapes and surfaces, including polish walls, sometimes covered in slip skid, and bases on which the pots could stand without being suspended by rope. Burnished surfaces, effectively incisions, and sturdy constructions that advise an interest in symmetry are characteristic of Yayoi pots.

Bronze bell (dōtaku 銅鐸), Yayoi menstruum, H. 126.5 cm (Saitama Prefectural History & Folklore Museum, Google Arts & Civilization)

Some studies suggest that Yayoi pottery is linked to Korean pottery of the fourth dimension. The Korean influence extends across ceramics and can be seen in Yayoi metalwork likewise. Notably, Yayoi period clapper-less statuary bells closely resemble much smaller Korean bells that were used to beautify domesticated animals such as horses.

These bells, together with bronze mirrors and occasionally weapons, were buried on hilltops. This practice was seemingly linked to ritual and may have been considered auspicious, peradventure for the fertility of the land in this primarily agronomical social club. The magical or ritualistic office of the bells is further suggested past the fact that the bells were not only clapper-less, but they likewise had walls that were too thin to ring when hit.

The bells became larger later on in the Yayoi flow, and it is believed that the function of these larger bells was ornamental. Across regions and over the bridge of a few centuries, such bells varied in size from approximately 10 cm to over i meter in height.

Kofun catamenia (ca. 3rd century – 538):

influential importations from the Asian continent (Ii)

The Kofun 古墳 period is so named afterward the burial mounds of the ruling class. The do of building tomb mounds of monumental proportions and burying treasures with the deceased arrived from the Asian continent during the 3rd century. Originally unadorned, these tombs became increasingly ornate; past the 6th century, burial chambers had painted decorations. The burial mounds were encircled with stones; hollow clay earthenware, known in Japanese every bit haniwa 埴輪, were scattered for protection on the land surrounding the mounds. Kofun were typically keyhole-shaped, had several tiers, and were surrounded past moats. The resulting structure amounted to an impressive brandish of ability, advertising the control of the ruling families. The largest kofun is the Nintoku mausoleum, measuring 486 meters!

The Nintoku mausoleum in Sakai, Osaka prefecture, Nihon, part of the Mozu-Furuichi group of ancient burial sites known as kofun (image: KYODO, Japan Times)

The hollow clay objects, haniwa , that were scattered around burying mounds in the Kofun flow, have a fascinating history in their own right. Initially simple cylinders, haniwa became representational over the centuries, commencement modeled as houses and animals and ultimately as homo figures, typically warriors. The later pieces have been of smashing help to anthropologists and historians as tokens of the material culture of the Kofun period, offering a glimpse into that society. Whether offerings for the dead or protective barriers meant to guard the tombs, haniwa have a strong aesthetic identity that continues to be a source of inspiration for Japanese ceramists.

Haniwa. Left to correct: Cylindrical haniwa, 5th century, excavated in Kaga-shi, Ishikawa, earthenware (Tokyo National Museum, image: Steven Zucker); haniwa firm, 5th century, excavated in Sakura-shi, Nara, earthenware (Tokyo National Museum); haniwa horse, 5th-sixth century, Japan, earthenware, partially restored, H. 94 cm (Tokyo National Museum); haniwa of a female shrine bellboy, 6th-7th century, Nippon, earthenware, 88.9 cm loftier (Yale University Fine art Gallery)

Shallow cup on alpine pedestal foot, Kofun period, 6th century, Japan, Sue ware, unglazed stoneware, H. 15.1 cm (Souvenir of Charles Lang Freer, F1907.525, Freer Gallery of Fine art)

Through gradual consolidation of political power, the Kofun-period Yamato clan became a kingdom with seemingly remarkable command over the population. In the fifth century, its center moved to the historical Kawachi and Izumi provinces (on the territory of nowadays-day Osaka prefecture). It is at that place that the largest of the kofun burying mounds testify to a thriving Yamato social club, one that was increasingly more than secular and military.

Simultaneously, the potter's wheel was used for the start fourth dimension in Japan, likely transmitted from Korea, where it had been adopted from Cathay. This new engineering science was used to produce what is known as Sue ware—typically blue-grey or charcoal-white footed jars and pitchers that had been fired in sloped-tunnel, single-bedchamber kilns (anagama 穴窯) at temperatures exceeding ane,000 degrees celsius. Like other types of ancient Japanese pottery, Sue ware continues to be a source of inspiration for ceramists, in Nippon and beyond.

Asuka menses (538-710):

the introduction of Buddhism

The Asuka period is Japan'south first historical menstruum, different from the prehistoric periods reviewed then far considering of the introduction of writing via Korea and China. With the Chinese written language too came standardized measuring systems, currency in the grade of coins, and the do of recording history and electric current events. Standardization and record-keeping also encouraged the crystallization of a centralized, bureaucratic government, modeled on the Chinese.

All this was imported when a new faith—Buddhism—was introduced in Japan, significantly changing Japanese civilization and society. Unlike Japan'due south indigenous "way of the gods" (Shintō), Buddhism had anthropomorphic representations of deities. Afterward the introduction of Buddhism, nosotros meet a shift in the visual and cloth civilisation of Shintō. If, before Buddhism, Shintō gods were associated with sacred objects such as mirrors and swords (the royal insignia), subsequently the introduction of the new faith they began to be represented in anthropomorphic images, although such images were subconscious in the inner sanctuaries of Shintō shrines.

By the time Buddhism reached Japan, information technology had spread from India to China and had undergone several changes in imagery and styles. In Japan, Buddhism profoundly influenced ethnic culture, but it was equally shaped by it, resulting in new forms and modes of expression. The majestic household embarked on major Buddhist commissions. One of the primeval and most spectacular is a temple in Nara, Hōryūji or the "temple of flourishing constabulary." The founding of Hōryūji is attributed to the ailing emperor Yomei, who died before seeing the temple completed; Yomei'southward consort, empress Suiko, and regent Prince Shōtoku (574-622) carried out the tardily emperor's wishes. Given the influence of empress Suiko's Buddhist patronage, the Asuka period is also referred to as the Suiko flow. Prince Shōtoku, too, is celebrated as one of the earliest champions of Buddhism in Japan. In fact, a century subsequently his death, he began to be worshipped as an incarnation of the historical Buddha.

Entasis columns, Chūmon kairō (curtilage-gallery of Central Gate), mid-6th century – early 8th century, Hōryūji (epitome: Hōryūji, Nara)

Similar the enduring legend and legacy of Prince Shōtoku, Hōryūji has had a long and complex life well by the Asuka Menses. With structures that vanished in fires and earthquakes equally early as the 7th century to the temple's pagoda that was dismantled and reassembled during World State of war 2, Hōryūji underwent numerous changes and its buildings currently date from the Asuka period to the late 16th century! A complex site with some of the earth's oldest wooden structures, Hōryūji exemplifies ancient Japanese architectural techniques and strategies, including the slight midpoint bulging of round columns, which has been compared to the similar do of entasis in ancient Greek architecture.

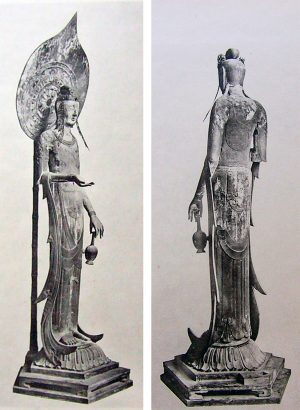

Front and back views from earlier 1917, Kudara Kannon, carved seventh century, camphor woods, Hōryūji, Nara (image adjusted from: Wikimedia Eatables)

Hōryūji houses one of the best known, admitting mysterious, Buddhist representational sculptures of the Asuka menses—the and then-chosen Kudara Kannon 百済観音, a slim and life-size image of the bodhisattva of compassion, sculpted in camphor wood. The first cultural property in Nihon to exist designated as a "national treasure," this sculpture first appeared in Japanese records in the 17th century. The "Kudara" in its proper name, assigned well afterward the Asuka menstruation, is the Japanese term for Baekje, one of the iii historical kingdoms of Korea. The sculpture'south phenomenal grace derives from its slight grin, slim frame, and flowing lines.

Face and right hand of Smashing Buddha of Asuka, c. 609, cast bronze, 9 anxiety high (Asuka temple, image: Wikimedia Commons)

Hōryūji was not the only major temple adult in the Asuka period. When the capital was transferred from Asuka to Nara, a temple known as Hōkōji was relocated too. In its new location, the temple grew significantly nether the proper noun of Gangōji. 1 of the temple's treasures is the Asuka daibutsu 飛鳥大仏 or the Groovy Buddha of Asuka—a devotional image that testifies to the early Buddhist representational tradition in Japan. It is as well the oldest of the daibutsu or 'dandy Buddhas'—large sculptural devotional images of the Buddha.

Of the original, bandage in 609 and attributed to a sculptor of Korean descent, merely the confront and the fingers of the right mitt remain. These details, withal, reveal the Chinese-inspired mode of Tori Busshi, with soft features, smooth surfaces, and unproblematic and elegant lines.

The four Heavenly Kings (Shitennō 四天王), Hakuhō period, painted forest, roughly 133.5 cm high (Hōryūji, image adapted from: j_butsuzo)

The late Asuka period, also referred to as the Hakuhō period (tardily seventh century), saw a momentous transformation of Japanese society, prompted past the and so-called Taika reforms. Implemented after the decease of Prince Shōtoku, these reforms were modeled on the Chinese system of government and led to a greater centralization of Japanese imperial power. In the realm of Buddhist sculpture, the Hakuhō catamenia marked a rapid expansion and dissemination of Buddhist imagery beyond Japan. Full-bodied sculptures, similar the four Heavenly Kings at Hōryūji, are more visually assertive than the Kudara Kannon and announce the influence of Tang-dynasty Chinese culture. In that, the Hakuhō flow tin besides be considered the starting time segment of the subsequent era—the Nara period.

Nara period (710-794):

the influence of Tang-dynasty Chinese civilisation

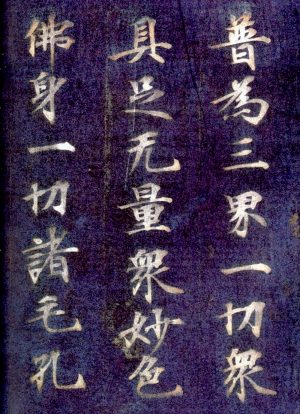

Fragment of the Flower Garland Sutra, known as Nigatsudō Burned Sutra 二月堂焼経, c. 744, silver ink on indigo-dyed newspaper, 9-three/4 inches loftier (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Mainland china'south Tang dynasty concentrated such a various range of foreign influences that its artistic and cultural characteristics are ofttimes referred to as the "Tang international style." This way had a major impact in Japan as well. Featuring an eclectic and exuberant mix of Cardinal Asian, Persian, Indian, and Southeast Asian motifs, Tang-dynasty visual culture comprised paintings, ceramics, metalware, and textiles.

As these strange imports were shaping Chinese artistic expression at home, Tang-dynasty artifacts and techniques spread beyond China to neighboring states and along the Silk Road. In Japan, the lavish Tang style was intertwined with Buddhist devotional art.

Elegantly transcribed sutras, calligraphed in argent ink on indigo-dyed newspaper, exemplify this grade of Tang-inspired Nara-menstruum art. The painstaking do of copying Buddhist sacred texts by using precious materials was deemed to earn spiritual merit for everyone involved, from those preparing the materials to the patrons.

The intermingling of political power and Buddhism in the Nara period found its utmost expression in the edifice of the "groovy eastern temple" or Tōdaiji and, within this temple, in the casting of the "great Buddha"—a gigantic bronze statue that stood approximately xv meters/ 16 yards tall and necessitated all available copper in Japan to produce the casting metal.

The Peachy Buddha (daibutsu 大仏), 17th century replacement of an 8th century sculpture, Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan (photo: throgers, CC By-NC-ND 2.0)

Although the current statue is a later replacement of the Nara-catamenia artifact, it all the same suggests the effect of opulence and awe that it must have achieved in its solar day. Tōdaiji connected to transform and suit through the centuries, just its identity is still inextricably linked to the chiliad calibration and commensurate appetite of Nara-flow civilization.

Sociopolitical power was full-bodied, during the Nara menstruation, in the new Heijō majuscule (today's urban center of Nara). Surrounded by Buddhist temples, the Heijō palace was the principal site of majestic power. It also housed subsidiary ministries, modeled on the Chinese centralized regime. Generous spaces characterized the palace complex. These spaces accommodated outdoor celebrations, similar those of the New year, only too served to emphasize a sense of distance and therefore the due reverence to the emperor. The palace complex was designed to separate the realm of the emperor from the exterior globe. That principle of separation was reflected within the palace compound itself, where the emperor's living quarters were set apart from authorities buildings. The architectural configuration of the palace reflected the hierarchical configuration of power.

Little of the palace survives today, equally various structures inside the complex suffered the vicissitudes of nature and history, while others were transferred to the new capital, Heian, for which the next period was named.

Heian period (794-1185):

courtly refinement and poetic expression

The new capital, Heian or Heian-kyō, was the metropolis known today equally Kyoto. In that location, during the Heian period, a lavish culture of refinement and poetic subtlety developed, and it would have a lasting influence on Japanese arts. The approximately four centuries that comprise the Heian period can be divided into three sub-periods, each of which contributed major stylistic developments to this culture of courtly refinement. The sub-periods are known as Jōgan, Fujiwara, and Insei.

The so-chosen Jōgan sub-period, spanning the reigns of two emperors during the 2d half of the 9th century, was rich in architectural and sculptural projects, largely spurred by the emergence and development of the two branches of Japanese esoteric Buddhism. Two Buddhist monks, Saichō and Kūkai (besides known as Kobo Daishi), traveled to China on study missions and, upon their respective returns to Japan, went on to found the two Japanese schools of esoteric Buddhism: Tendai, established by Saichō, and Shingon, established by Kūkai.

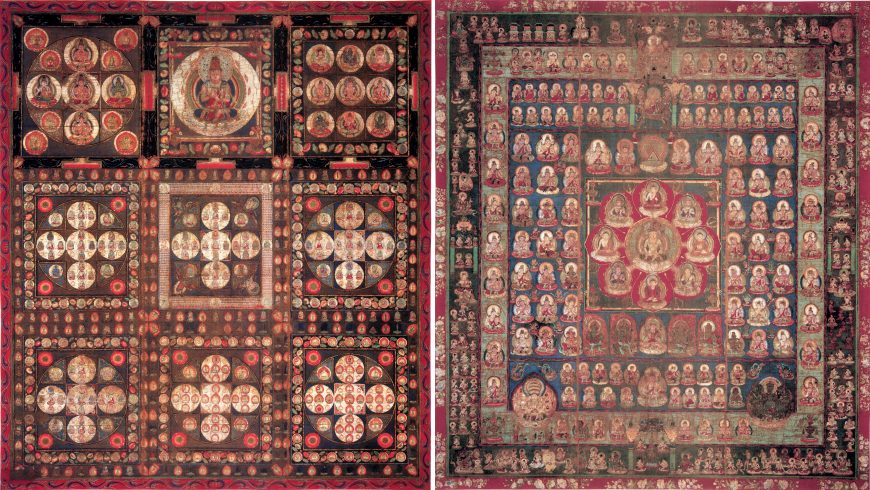

Ryōkai mandala 両界曼荼羅 ("the mandala of the two worlds"). Left: Kongōkai mandala 金剛界曼荼羅 (diamond realm mandala); right: Taizōkai mandala 胎蔵界曼荼羅 (womb realm mandala), 9th century, color on silk, 183 ten 154 cm (Tōji, Kyoto, image: adjusted from Wikimedia Commons)

In Esoteric Buddhist ritual, the Womb realm mandala is hung on the E wall, while the Diamond realm mandala is hung on the West wall. The mandalas face each other.

Amid the many ideas and objects that they had brought dorsum from China was the Mandala of the 2 Worlds, a pair of mandalas that represent the central devotional image of Japan's schools of esoteric Buddhism. Comprised of the "Womb World Mandala" (mandala of principle) and the "Diamond World Mandala" (mandala of wisdom), the Mandala of the Two Worlds was showtime assembled equally a pair past Kūkai'due south teacher in Mainland china. One such pair, still housed in Kūkai's temple in Kyoto (Tōji, the "eastern temple") represented a blueprint for countless mandalas made in Nippon over the centuries.

It is believed that the consequential trip to Prc of Saichō and Kūkai was enabled past a member of the Fujiwara, the family that gives the name of one of the Heian sub-periods. The influence of the Fujiwara clan was paramount in the Japanese political and artistic world of the ninth and tenth centuries. Their ability was bolstered past the ever-growing shōen system and ensured by their control of the majestic line, every bit Fujiwara daughters were married to imperial heirs.

Phoenix statue on roof of Phoenix Hall, replaced in 1968 (image: Byōdō-in)

I of the simply surviving structures from the Fujiwara period, the Phoenix Hall of the Byōdō-in (a Buddhist temple in Uji, outside Kyoto) is one of Japan's about valuable cultural avails, with a fascinating, multi-layered story. The Phoenix Hall derives its proper name from the statues of phoenixes—auspicious mythological birds in E Asian cultures—on its roof.

Completed in 1053, the Phoenix Hall was sponsored by a member of the Fujiwara family—Fujiwara no Yorimichi—a pious believer in all the same another type of Buddhism, known as Pure Land. This occurred at a time when many imperial villas like the Byōdō-in were converted into Buddhist temples. Having spread to Japan through the efforts of the monk Hōnen, the Pure Land School of Buddhism taught that enlightenment could exist achieved by invoking the name of Amida, the Buddha of infinite light. Practitioners engage in the ritualistic invocation of Amida's proper name—the nenbutsu 念仏—hoping to be reborn in Amida'due south Pure State, or the Western Paradise, where they can continue their journey towards enlightenment undisturbed.

Jōchō, Amida, 1053, gilt wood (Byōdō-in, Uji, Japan, image: Byōdō-in)

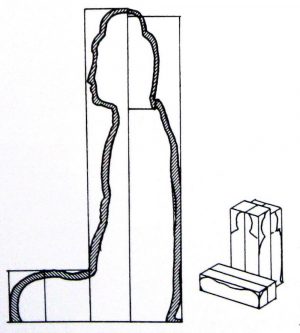

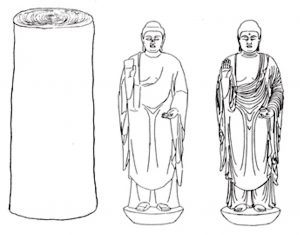

Yosegi-zukuri 寄木造 technique. Different parts of the sculpture are independently carved from multiple wood blocks, and then joined (image adapted from: kanagawa-bunkaken)

Ichiboku-zukuri 一本造 technique. Left to right: cake of woods; sculpture carved in crude form out of the wood block; fine details are farther carved (image adapted from: Nara National Museum)

The Amida sculpture in the Phoenix Hall at Byōdō-in is the but work nevertheless extant by Jōchō, an influential sculptor who was awarded remarkable distinctions, worked on various commissions from the Fujiwara family, and organized fellow sculptors into a guild. Jōchō's Amida at Byōdō-in reflects the sculptor'south yosegi-zukuri 寄木造 technique, in which the sculpture is formed from multiple joined pieces of forest. This technique was different from the ichiboku-zukuri 一本造 technique, co-ordinate to which the sculpture is carved out of a unmarried block of forest.

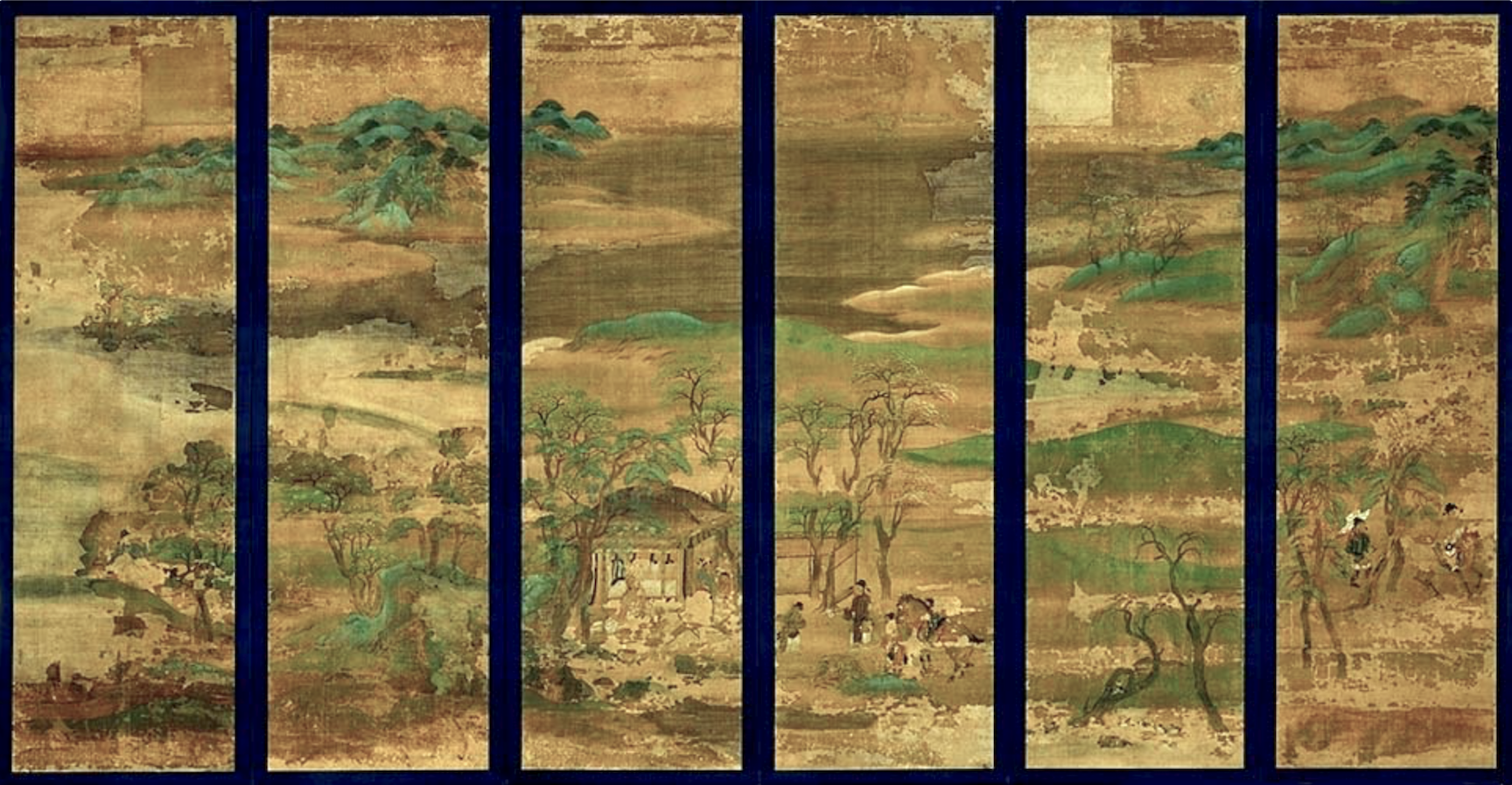

During the Heian period, the style known as yamato-e (大和絵 or 倭絵) is born. Understood as "Japanese" every bit opposed to "Chinese" or otherwise "strange," yamato-due east encompasses a wide range of technical and formal characteristics but refers to specific formats—folding screens (byōbu 屏風) and room partitions (shōji 障子)—and specific choices of subject matter—landscapes with recognizably Japanese features and illustrations of Japanese poetry, history, mythology, and folklore.

Ane of the primeval examples of Heian-period yamato-e landscape painting. Senzui byōbu 山水屏風 (lit. "folding screen(s) with (imagery of) mountains and waters), six-fold screen, 11th century, color on silk, 146.4 x 42.7 cm, designated National Treasure (Kyoto National Museum)

Detached segment of illustrated curlicue of the Tale of Genji, 12th century, opaque colors on newspaper (Tokyo National Museum)

A favorite subject for late-Heian-period yamato-east was the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 源氏物語), written in the commencement years of the 11th century and attributed to a lady-in-waiting at the purple court, Murasaki Shikibu. A complex novel that focuses on the romantic interests and entanglements of the prince Genji and his entourage, the Tale also provides a fascinating entryway into Heian-menstruum court life, complete with the artful principles and practices that resided at its core.

The earliest illustrations of the Tale came in handscroll format. Surviving fragments exemplify the yamato-e mode of narrative painting: illustrations by episode interspersed with passages of text; roofless buildings, multiple viewpoints (typically both frontal and from above), and schematic renditions of faces ( hikime kagihana 引目鈎鼻, literally translated as "drawn-line eyes, hook-shaped nose.")

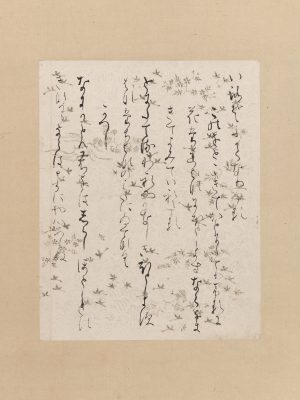

"Lady Ise Collection", poetry calligraphy, early 12th century, book page mounted every bit hanging curl, ink on decorated paper (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A brief review of the Heian menstruum cannot be complete without mention of the evolution of Japanese poesy, waka in detail. Waka was an integral part of the Tale of Genji, and Murasaki Shikibu came to be known as i of the half dozen immortal poets (all of whom were from the Heian period).

Permeating the spirit of Heian-period Japanese verse and the imagery it inspired was a heightened sense of refinement, expressed in elegant poesy, stylized visual motifs, precious materials, and embellished surfaces.

The Insei rule—the third and last of the Heian sub-periods —refers, literally, to the royal do of ruling from inside a (monastery) compound. During Insei, cloistered emperors had a college degree of political control. It was during this flow that a sense of aesthetic and ethical congruence developed, co-ordinate to which the beautiful and the good are intrinsically interconnected.

Additional resources

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

due east-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and of import cultural backdrop

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art'southward Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge Academy Press, 1993)

Cite this folio equally: Dr. Sonia Coman, "A cursory history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods," in Smarthistory, December 2, 2019, accessed April 25, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/nihon-jomon-heian/.

hollowellmathesembed.blogspot.com

Source: https://smarthistory.org/japan-jomon-heian/

0 Response to "Origins of Shingon Buddhist Art Using Gold and Clouds"

Post a Comment